Author: Eric Griffith

Review Date: 1/20/2005

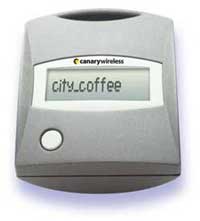

Model: HS10

Price: $49.95

Pros: Tells all about nearby networks.

Cons No backlight, too bulky for a keychain, can’t detect certain APs.

When it comes to detecting wireless 802.11b/g networks without a computer, the Canary Wireless Digital Hotspotter is the real deal.

Up to now, signal locators have consisted of units that, when you push a button, an LED or series of LEDs illuminate to show you that a network is there and (depending on the product) what the signal’s strength is.

The downside of those first generation products is that you don’t know if the network is open or encrypted with security until you get out your Wi-Fi device to try and log in. There’s nothing more disappointing that going through the entire boot up only to find out you can’t check your e-mail.

That’s where DigitalHotspotter differs. Instead of just having lights to tell you if a network might be available, it shows you a wealth of information about each WLAN it can detect. The data includes a scrolling 12-character LCD showing the network’s broadcasting SSID (it will say “Cloaked” for networks not broadcasting the ID); a rating of signal strength (one to four bars); whether encryption is in use with either wired equivalent privacy (WEP) or Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA), shown as either Open or Secure; and even what channel the signal is broadcasting on (1 to 11 in the US or 1-13 in Europe).

It does not differentiate whether the network is 802.11b or 802.11g, and it doesn’t detect 5GHz 802.11a networks at all. Nor will it work with future standards like 802.11n.

But does it work like it is supposed to? With aplomb.

In a trip around my city the DigitalHotspotter showed itself to be the tool wardrivers who really don’t care about getting into other people networks really want. On one side street I found no less than three open networks within 100 feet. In a restaurant across the street from a UPS Store, the SBC FreedomLink network gave a strong signal. The local ISP setting up its own hotspot network had good coverage far outside the venues it advertises— each showed a unique SSID that incorporated the name of the business.

Once the Hotspotter detects a network, you just again push its single button to cycle to the next network in range, if one exists.

Keep in mind that a network listed as Open doesn’t mean you can automatically get online with it. A commercial sounding name like “t-Mobile” should be a give away—they will let you one, but you’re going to get forwarded to a Web page where you can sign up to pay for service. Plus, there is always the possibility of interference, or of another type of security being used such as MAC filtering or 802.1X authentication.

Signal locators are interesting to use when testing for the range of your own network’s signal. I found with certainty that I can probably use my laptop on my back deck, but not my front porch, likely due to the position of my wireless router. It was like a mini site survey.

Other signal locators—like the Chrysalis WiFi Seeker, our previous favorite in this category— have claimed in the past to be able to tell the difference between a Wi-Fi signal in the 2.4GHz frequency and that of, say, a microwave oven or cordless telephone using the same unlicensed spectrum. DigitalHotspotter most definitely does not see non-802.11b/g signals—and it won’t even find access points that are set just to bridging, nor Bluetooth-based products.

The company does admit that the unit is not fool-proof however. The troubleshooting forums on the Canary Wireless Web site say “a small number of access points have a default configuration that makes the access point hard for the device to detect.” This is sometimes caused by broadcasting beacon frames at too high a rate to be detected. They suggest power cycling any access points you know should be found, or setting the data rate lower if it’s adjustable. However, a list of APs it just won’t detect include the Linksys BEFW11S4, D-Link DI-614+, Cisco 1200, Zyxel B-4000, and Colubris 3200.

The forums also say that with an average of one or two scans a day the batteries in the Digital Hotspotter should last around two months. The company admits that it initially ships with “starter batteries” (aka, el cheapos) with a low charge. Luckily, the unit takes simple AAAs which are easily replaced via a slot in the back, like you’d find on any remote control. When the juice is low the unit will tell you with a “low battery” warning. You don’t have to turn it off—it does that after 30 seconds of inactivity (meaning no one pushes the button again).

If you can live with the above limitations, the product only has three other faults, all minor:

- It’s too big to fit comfortably on a key chain. The Hotspotter measures 2.52 inches at its longest, and is over 1 inch thick. It does have a narrow slot to fit a key ring through, but the company says that metal placed under that arch could interfere with the antenna below it. Obviously, we were spoiled by the size of the Chrysalis design, but the Hotspotter is still smaller than all the previous first generation signal locators except the Chrysalis.

- Hotspotter has no backlight on its tiny LCD, which is annoying at best in low-light conditions.

- Finally, the unit is almost double the price of the competition at $50 direct from Canary Wireless. However, that price is still far less than any other handheld unit you’d have to use today to get the same information.

For the second generation of signal locators, the Digital Hotspotter has made a huge stride ahead of the LED-based competition. As the chips get smaller and cheaper, it’ll be fascinating to see where generation three goes (interpreting beacons? DHCP clients? Pings to the Internet? The mind boggles). The Hotspotter isn’t a guarantee, but it can provide reasonable confidence that the open network(s) it detects will get your main Wi-Fi device online.

Review originally appeared on Wi-Fi Planet.com