Author: Michael Hall

Review Date: 4/17/2007

Silly boy you got so much to live for

So much to aim for, so much to try for

You blowing it all with paranoia

You’re so insecure you self-destroyer

– The Kinks “Destroyer”

I thought of those lyrics about five minutes into my first session with Objective Development’s Little Snitch, a Macintosh network monitoring tool that, as its Web page promises, “alerts you on outgoing network connections.” But don’t take that lyrical snippet as a sign of disapproval over the product, just take it as a cautionary bit of advice you’ll want to keep in mind before you embark on what will be a brief period of learning what a sausage factory of outbound network connections modern Mac software is. We’ll get back to that.

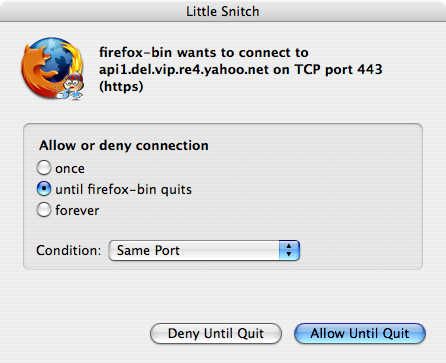

As Little Snitch’s developers promise, it “alerts you on outgoing network connections.” What that means is that each time a program running on your system tries to send traffic over a network interface, Little Snitch notices, stops the traffic and tells you. That’s handy. Handier yet, Little Snitch will offer a variety of choices for dealing with that connection — from denying that app access to the Internet for all time to letting it have carte blanche.

Here’s a list of apps that set Little Snitch off in the first ten minutes I used it. Some are obvious, because their raison d’être is Internet access. Others might momentarily surprise you:

- Adium (IM — that’s a no-brainer)

- Firefox (yeah — I can see that one)

- iCal (Really? Oh … right … shared calendars)

- Ecto (blogging software … though I haven’t touched it for, like, six hours)

- TextSoap (this is getting weird)

- BBEdit (but it’s a TEXT EDITOR!)

And that’s the truncated list. But Little Snitch logged them all and let none of their traffic pass from my computer until I okayed it. Tirelessly. Ceaselessly.

As I noted, some of those apps have an obvious need to talk to the ‘net because that’s what they do for a living. Text editors and formatting software, though? Well … yeah. Because even if they don’t need to talk to the network to do what you use them for, they’re probably talking to their developers to see if there’s a new version available for you to download (using, for instance, the Sparkle module) or even (though not, as far as I know with BBEdit or TextSoap) to verify your licenses.

Now, I’m aware I probably sound a bit snippy here … I install a thing that’s supposed to tell me about network traffic, then act all bent out of shape and put upon when it does what it says. But that period of initial irritation fades pretty quickly once you go through an hour or two of use, because by then you’ve probably gone ahead and whitelisted the apps you expect to access the Internet, or trust. VoodooPad, for instance? I trust its developer.

White- (or black-) listing is a simple process: Each time an app tries to go online, Little Snitch intercepts it and asks what you want to do with it. Your options include the following:

- Allowing or denying access once.

- Allowing or denying access until the application quits.

- Allowing or denying access forever.

You can choose conditions for each, too:

- Over any network connection.

- On the same port.

- To the same server.

- To the same server and port.

Once you’re through that process and most of your apps aren’t setting Little Snitch off anymore, you’re left with an intriguing list of attempted accesses that aren’t as obvious, sometimes pointing at servers that seem to have no relation at all to anything you’ve done.

Take, for instance, the screenshot on the left. Little Snitch is reporting an attempted access to “api.del.vip.re4.yahoo.net,” even though Firefox had been sitting idle, no windows open, for the past 30 minutes. Weird, huh? Why does it need to talk to Yahoo? And what’s with the obscure URL? I thought briefly that perhaps Yahoo’s toolbar, something I used briefly over a year ago, was somehow soldiering on in zombie form, but that just didn’t make sense. A few seconds of head-scratching later, though, and I got it: I use foxylicious with Firefox. It syncs up my del.icio.us bookmarks with my Firefox bookmarks. del.icio.us is owned by Yahoo, and the “api” bit at the front of the URL is, no doubt, because Foxylicious is using the del.icio.us API to sync bookmarks. Mystery solved.

Once you get the initial break-in period out of the way, though, Little Snitch’s reason for being becomes more manifest. It isn’t to annoy you with endless warnings about benign network access from apps you trust, it’s to warn you when something that probably shouldn’t be trying to send a few packets over the ‘net is doing so behind your back. Macs are mercifully free of spyware, but it could happen. And you might not be comfortable with the kind of information some software wants to phone home with.

The fact is, for most home and small office users, it’s a simple matter to lock down a computer against external threats. A $30 broadband router or a giveaway firewall app can handle that easily. OS X provides a firewall for free, in fact, right there in the “Sharing” preferences pane.

The problem these days is less about what gets in surreptitiously, but what tries to get out after you brought it in through the front door in the form of a seemingly harmless download. Little Snitch helps you keep an eye out for that sort of thing. You could also use it to avoid the risk of Web bugs in your spam reporting that you’re a good address to send things to. It might even stop a developer’s genuine flight of utter insanity, should he decide, as one did, that remotely deleting files is an appropriate response to an apparently pirated license.

Little Snitch does its job reliably, and ships with a default set of basic rules that cover exceptions necessary to keep your Mac running at all. It’s not just user applications that do a lot of talking over the network: Your Mac might be keeping accurate time using the Internet, and the CUPS service, which provides the printing subsystem in OS X, depends on a network socket. All the exceptions are listed at the Little Snitch Web site, and they’re worth reading on their own if you’re curious about what your Mac does behind the scenes.

But to get us back to that opening quote, here’s a caveat that shouldn’t keep you from experimenting with Little Snitch, but that warrants consideration:

You can make yourself crazy with paranoia. It is not at all uncommon to visit sites like VersionTracker or MacUpdate and find people posting comments that accuse apps of “malicious behavior” or “suspicious phone-home activity,” citing what’s most often a poor reading of Little Snitch’s reporting as the reason for their suspicions. The paranoia mounts as the name of the contacted server seems less and less obvious, like that foxylicious example I gave.

Spend too much time doing that and knowledge stops being power and starts being a real nuisance, especially for honest developers you’re calling out for the egregious behavior of making sure your software has the latest bugfixes. If you can’t live with that, unplug the cable modem and glue that tinfoil hat on. You weren’t meant to use a computer in the 21st century.

Little Snitch is available from Objective Development as a fully functional demo that has to be manually reactivated after three hours of continuous use. It installs as a preference pane. If you like it, it costs $24.95 for the unlimited version.

My recommendation? If you’re concerned about maintaining maximum privacy and security, $24.95 isn’t a lot of money, and Little Snitch’s overall interface and user experience is pretty unobtrusive once you get through the training period.

Even if you aren’t in the market for a tool like this, running it for a demo cycle or two is an educational experience.