Leopard’s Time Machine mission is built to protect you from accidental or ill-advised deletions for as long as your backup disk space holds out (or for 30 days). But from a security point of view, that behavior is bad.

I hate retractions and corrections, but one’s in order this week so I’m going to issue it and use it to wade into the issue it raises.

Last week I offered a brief review of Time Machine, the backup software that ships with Leopard. “If there’s one big ‘issue’ with Time Machine,” I wrote, “it’s this: You might end up going for a second external hard drive.”

Well, there’s a second big issue, uncovered by Steven Fisher, which is that Time Machine will run applications you thought you removed from your system if they once acted as a handler for the kind of file or URI you’re trying to access.

From a user convenience point of view, that behavior is very much in line with the Time Machine mission, which is to protect users from accidental or ill-advised deletions for as long as their extra disk space holds out (or 30 days). If I trashed the one app I needed to open an illustration or file, I’d be happy to have that app archived and waiting for me to ask for it again.

But from a security point of view, that behavior is not good at all. I’ll let Fisher explain it:

“Let me give you a simple example: You find out Adium (for example) has an available exploit that the developers haven’t patched yet. You remove Adium, but it continues to exist in your backup. You visit a Web page that activates the Adium bug, and Adium is launched from your backup.”

Depending on the nature of that bug and the page that activated it, you could be in for some hurt even if you did the right thing in the first place, which was to get rid of an application you knew to be insecure, and it’s a good thing that Macs aren’t on the receiving end of most automated malware attacks.

There are two remedies for this behavior:

- Time Machine includes the ability to remove all backups of something you’ve just deleted by using the gear menu while you’re in Time Machine. Tech Recipes illustrates how to do it.

- The Time Machine preferences pane (under System Preferences) also allows you to exclude a given volume or folder from backups by clicking “Options” and either dragging the item to be excluded into its list, or clicking the “+” button and adding it from the menu.

The former method is clunky but preserves the convenience of having backups of any non-dangerous apps you may have removed. The latter is more transparent but may cost you some convenience down the road.

As Fisher suggested, the opportunity to provide a real remedy lies with Apple, which should attach a warning dialog to any app it tries to execute from a Time Machine backup.

That mis-feature didn’t get much attention, though, because two other Leopard security stories reared their heads in the midst of all the post-launch euphoria.

The Firewall’s Funny Phrasing

First, Heise Security released a scathing indictment of Leopard’s built-in firewall. The report demonstrated that when Leopard’s firewall is active and set to “Block all incoming connections,” it is doing no such thing.

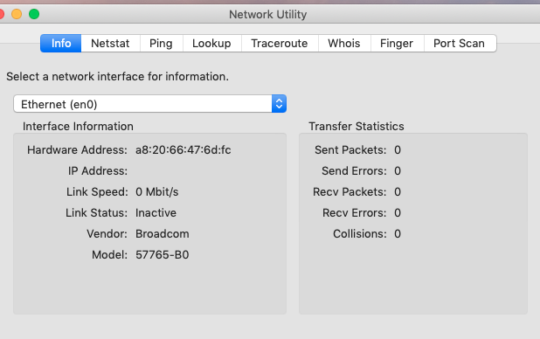

Consider, for instance, a Leopard box set up to share a printer along with file sharing via Apple’s AFP and SMB for Windows clients (as covered last week). Running a port scan on that machine without the firewall activated shows the following:

PORT STATE SERVICE Not shown: 1690 closed ports 22/tcp open ssh 88/tcp open kerberos-sec 139/tcp open netbios-ssn 445/tcp open microsoft-ds 548/tcp open afpovertcp 631/tcp open ipp 3689/tcp open rendezvous

Turn on the firewall, set it to “Block all incoming connections,” re-run the scan:

Not shown: 940 filtered ports, 750 closed ports 22/tcp filtered ssh 88/tcp open kerberos-sec 139/tcp filtered netbios-ssn 445/tcp filtered microsoft-ds 548/tcp filtered afpovertcp 631/tcp filtered ipp 3689/tcp open rendezvous

There’s a reason for that, which people quickly pointed out upon reading the Heise Security article: Apple decided preferences set elsewhere, such as file and printer sharing or remote shell connectivity, outweighed the firewall.

Depending on where you stand on Mac security (and whether Mac security itself is a scurrilous lie propagated by unreasoning hoards of fanboys), that choice is anything from merely bad phrasing on Apple’s part to an outrageous breach of trust, which the Heise Security article concluded:

“Apple is showing here a casual attitude with regard to security questions which strongly recalls that of Microsoft four years ago. Back then Microsoft was supplying Windows XP with a firewall, which was, however, deactivated by default and was sometimes again deactivated when updates were installed. It was also the case that system services representing potential access points for malware were accessible via the internet interface by default. Despite years of warnings from security experts, the predominant attitude was that security must not get in the way of the great new networking functions.”

And, as with the Time Machine issue, Apple can fix this easily enough with a little better information. The firewall configuration pane should be more up front about what it’s doing, and it might not hurt for Apple to introduce a fourth posture besides “on and generally strict,” “on with user-specified qualifications” and “off,” like “on and locked down so tight that printer you thought you were sharing will think it’s in Alcatraz,” with an accompanying warning that services enabled elsewhere (file and printer sharing, for instance) will be disabled at that setting.

Heise Security’s article also noted and took issue with the fact that Leopard’s firewall is off by default. That’s not good either. On the other hand, the site posted a followup article about how badly some applications break when the firewall is on, due to digital signing that affects checksums the applications themselves depend on to verify they haven’t been tampered with, which means using the firewall at all could be a user-discouraging hassle.

I suspect we’ll be seeing Leopard’s firewall in upcoming point release notes as Apple refines it.

Is Leopard 1998 All Over Again?

It’s funny Heise Security mentioned Windows, because security researchers were also clucking about a piece of professionally written, Mac-targeting malware that manifested in the wild last week, and darkly noting parallels with the bad old days of Windows 98 and XP.

Users visiting an apparent porn site were invited to download a QuickTime codec, the better to watch the porn. If they ran the installer (which required entering their administrative password), the malware hijacked their DNS settings and set up a cron job to ensure the settings stayed hijacked.

Word that there was actual Mac malware that wasn’t a proof of concept got a certain sort of commentator verklempt in very little time.

“Apple’s day has finally come, and Apple users are going to get hit hard … OS X is the new Windows 98,” said one researcher.

“On the heels of the poorly-secured release of Leopard, we now find that there is no perfect protection against human stupidity social engineering, even for a Mac user,” said another.

That kind of commentary is an understandable side effect of one of the more lamentable aspects of Mac advocacy — operating system advocacy from anyone besides Windows users, it seems — the braying, exploit-counting fanboy who thinks the presence of an Apple logo (or Tux, or Chuck) provides the same protective properties the Boxers thought existed in their red sashes. Who doesn’t want to see a blowhard proven wrong? You don’t even have to have an opinion about Macs (or Linux, or BSD, or whatever) to know you don’t like ignorant loudmouths.

But researchers who initially indulged in a little pointing and laughing eventually came around to admitting that the significance of this particular trojan was primarily its origin, not its design or effectiveness: A criminal enterprise had decided there might be some ROI in repurposing Windows malware to use against Macs. I don’t make predictions about this sort of thing and I’m not about to start now, but there’s no more writing on the wall than there was two weeks ago, before that trojan made its appearance.

More to the point, the nature of how computers are compromised is shifting. Microsoft’s Security Intelligence Report for the first half of this year says that in 2006, “classic e-mail worms” represented “95 percent of the total malware detected in e-mail.” The kinds of worms the report is talking about rely on problems with the underlying operating system’s overall security to do their work, exploiting problems with how the e-mail client and OS interact to propagate and function.

But the report goes on to say that, in early 2007, worms dropped to 49 percent of the malware found in mail as phishing and malicious iFrame attacks rose to 37 percent. Greeting card scams and trojan downloaders, which rely on some form of social engineering to propagate, made up the remaining 14 percent of e-mail-based threats. The company’s statistics on overall security issues handled by its own OneCare products indicates that backdoors, viruses and worms — threats that depend on bad security practices in the operating system to proliferate — claimed less than 5 percent of reported incidents each. Compare to adware and trojans, which claimed between 20 and 25 percent of the total problems identified.

In other words, Microsoft may well be cleaning up its overall security game to prevent the sorts of automated threat proliferation we all remember from worms like Code Red or Slammer, but the people cooking up the threats are modulating their attack and figuring out ways to get users to make bad decisions that reduce their security. The company concluded its report with this observation:

“Social engineering and sub-optimal trust decisions are major factors in distribution of potentially unwanted software, with a prime example being the use of ActiveX controls. Social engineering attacks also continue to increase, attempting to deceive the user into installing unwanted software, following a malicious link, or otherwise taking action that may prove harmful. These attacks leverage many Internet technologies and may be transmitted via e-mail, instant messages, or left as posts to message forums or Web blogs.”

Does Microsoft have a motive to claim the nature of most security problems is shifting to problems that have less to do with poorly designed operating system security and more to do with “sub-optimal trust decisions”? Sure it does. But its observations about the growing prevalence of social engineering attacks are echoed by security companies as well, who arguably have more to lose by pointing out how much further common sense and a little paranoia will go in protecting users than the sort of automated solutions they sell. And just studying product lines, it’s clear that security companies are emphasizing protection from phishing and other social engineering attacks more and more with each release.

The Moral of the Story

So what does all this mean for Leopard?

First, it’s important to note that Apple added some useful security measures this time around.

Some are obvious: You can’t run a file you downloaded from the Internet without being reminded of where the file came from and being asked if you’re sure you want to open it. That kind of challenge hasn’t done Windows users a lot of good, but it’s better than nothing.

Some are less obvious: Improved authentication for access to NFS shares, improved SMB/CIFS security, improved network printing security, signed applications, and library randomization. The jury’s still out on how well Apple has implemented some of these features, but Leopard deserves some recognition for moving forward from Tiger.

Leopard also addressed the issue of Input Managers … little programs that alter the way applications work, sometimes in very subtle ways. TidBITS delved into why Input Managers might just be of the devil early last year, and Apple has made their use much more difficult in Leopard. It was frustrating to spend a few days waiting around for developers of legitimate Input Managers to figure out how to reimplement them in Leopard, but it’s good that they’re in better check, and it’s a whole lot better than what TidBITS’ own conclusion last year, which suggested “muddling along as usual, hoping that Mac OS X is reasonably safe under most circumstances.”

But from last week’s stories alone, it’s clear Apple has at least three practices it needs to reconsider:

- Users should not be able to run potentially dangerous applications from Time Machine without being asked first.

- The firewall should probably be operating out of the box upon install. It should not turn itself off for upgrading users who were using it.

- The firewall preferences should provide more accurate information about the computer’s actual network security profile.

But is Leopard a step backwards overall? Or more dangerous to users than previous OS X releases? No. Not in any way anyone has demonstrated.

Michael Hall has been using, maintaining and writing about networks for nearly 15 years. He’s the managing editor of Enterprise Networking Planet and he blogs about Internet privacy and security at Open Networks Today.